He bounds into the classroom, slightly out of breath, and snickering erupts above class-room chatter. This respected 36-year-old professor is the undisputed favorite among entomology students at Colorado State University. Just one glance at his red high-top sneakers, laced ankle-high under a three-piece suit, suggests why. This "insect Einstein," as one of his students has called him, is hardly your average university lecturer.

For a Ph.D. entomologist who wears the same getup to university business meetings, but whom gardeners and colleagues nominate as state Extension specialist of the year, there's an endless stream of descriptive adjectives. They flow the length of the alphabet-from credible, dedicated, dynamic and hard-working to outrageous, willing-to-try-almost-anything and zany. Whitney Cranshaw is definitely one of a kind.

The scientist has an uncanny gift for distilling technical Extension research into simple, albeit unconventional, solutions for back-yard pest problems.

Take his study on beer-imbibing slugs. "Gardeners kept asking why beer captured slugs, and I had no idea," he says. "I didn't know if it was the yeast or the alcohol that attracts them, or if the whole thing was just an excuse for a nip in the garden."

With only one way to find out, he decided it was time for a serious scientific showdown. Time, at last, to answer the question that no one else even thought to ask. Time to determine the beer that slugs are most willing to die for. Time for-drum roll, please- "Slug Fest '87: The Battle of the Breweries."

It was during a slow period two springs ago that Cranshaw finally found the perfect slug-infested site. Near the university in Fort Collins, a colleague's lush back-yard was oozing with them. Using tap water as a control, he and a few students proceeded to compare 12 of America's best-selling beers, a non-alcoholic "near beer," a pink chablis, and sugar and yeast in water for their attractiveness to slugs.

With scientific precision, they replicated each trial four times. Naturally, capture ratios were expressed in "Bud Units," a precise reflection of slugs' preference for other beers vs. America's No.1 seller, Budweiser.

By the time the last call was sounded some eight weeks later, nearly 4,000 slugs had taken the plunge, drowning in one liquid or another. The surprise winner? The king of near beers-Kingsbury Malt Beverage. Among slugs, anyway, Budweiser's popularity slipped from first to third place, right behind Michelob. As for the debate over Miller Lite (which, after years of televised arguing, some of America's greatest beer-slugging athletes still can't seem to clear up), the slugs had no trouble choosing. They prefer its "less-filling" promise to its "great taste," which proved about as attractive as sugar-water and yeast.

So then if it's not the alcohol that lures slugs, what is it? "A follow-up study revealed that it's the fermentation of yeasts, especially lager brewing yeasts," Cranshaw concludes.

He plans to take the study a step further some day. "But frankly, we got so many slugs out of the last site that I ruined the whole plot as a test site," he explains. "Experiments with other beers and fermented beverages aren't possible without a new one.

"If you can't beat 'em, eat 'em" is Cranshaw's rallying cry.

Not all of Cranshaw's research draws the laughs that the slug study does, of course. His insect studies are diverse and prolific, almost always drawing respectful praise from colleagues. "In his relatively short tenure [five years] at Colorado State, Cranshaw has prepared more Extension resource materials than many specialists achieve in their entire career," says Jim Feucht, a 22-year CSU professor and Extension landscape specialist.

Besides teaching entomology at Colorado State University and solving backyard pest problems through scientific study, Cranshaw educates gardeners about beneficial insects through Extension Service bulletins.

Cranshaw's overall performance impressed some master gardeners and Extension specialists so much that they nominated him for the state's annual distinguished service award last year, an uncommon honor after only five years' work. They cited his enthusiasm, humor, creative research and "seemingly endless source of energy regarding his profession" as an inspiration to their own work.

That's not to say that his wit inspires everyone. "His remedies don't always fit into mechanized agriculture, which sometimes miffs a few people," says John Capinera, former chairman of the entomology department at CSU.

But Cranshaw just shrugs it off. Aware that his offbeat slug study and those like it aren't typical of Cooperative Extension Service research, he's careful to draw funding for such projects from his own pocket.

In any case, "pest control" is only one dimension of his profession. Teaching gardeners to appreciate-not kill-insects is the other. In fact, two of his better-known Extension bulletins aren't about pest control at all. Instead, they stress the value and enjoyment of attracting beneficial insects and butterflies to the garden. When he does recommend pest remedies, which is pretty often as an Extension agent, he plugs the use of insecticidal soap sprays and biological controls whenever possible.

Cranshaw's interest in entomology and alternative pest remedies developed side by side when he was an undergraduate in environmental sciences at "the hippie college, near the end of the crash-pad era," as he puts it. Loosely translated, he attended Hampshire College in Amherst, Mass., near where he grew up outside of Boston, in the early 1970s.

The environmental movement was in full swing then, and bugs were making headlines. "DDT had recently been banned, pheromones were fairly new, biological control was getting a lot of press and IPM [integrated pest management] was the new buzzword," he recalls. So despite a 120-year tradition of Harvard-trained medical doctors in his family, he decided to spend his years studying insects.

"It was exciting then, and it's still exciting," he says, calling to mind his second humorous and non-toxic pest remedy. With a vengeful grin, he growls out the words that white lawn grubs everywhere fear to hear: "Remember the 'spikes o' death."'

SPIKES O' DEATH

"The chafer grubs around here are so big and tough to kill that I've actually seen people pouring chlordane on their lawns to purge them!" Cranshaw exclaims.

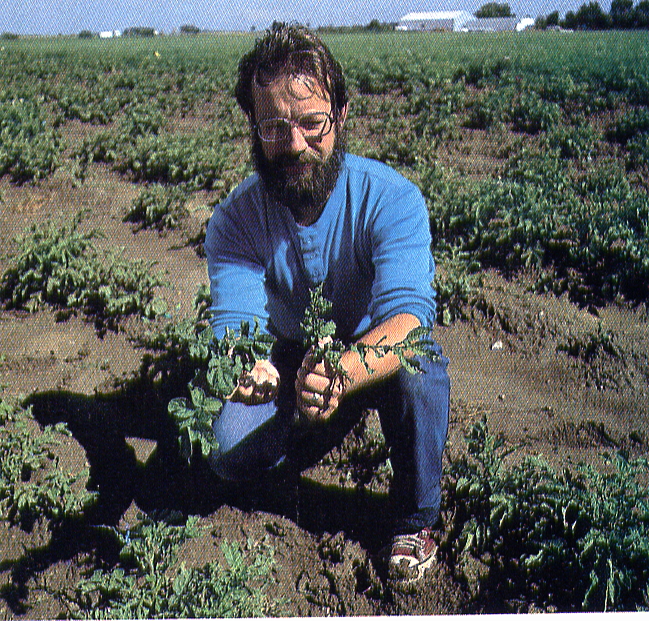

Diazinon is the widely used chemical that's legal for use against chafer grubs, which feed on grass roots an inch or two below ground. In 1986, Cranshaw eyed something else that might work as well as any pesticide, a non-toxic Jekyll-and-Hyde remedy for white lawn grubs. The Mellinger seed catalog referred to the product as humble "lawn aerator sandals," 3-inch-spiked sandals strapped on before mowing to aerate compacted lawns. But on this entomologist's feet, they're suddenly transformed into the "spikes o' death," as Cranshaw calls them, spiked aerator sandals worn to spear underground grubs.

In no time, another slapstick-style experiment with serious consequences for gardeners was underway. Students were soon spraying diazinon on infested patches of a grub-ridden lawn in Lamar, Cob., near the Texas border. Meanwhile, Cranshaw slipped on a pair

of sandals and walked-and walked. When the turf was finally pulled up and the number of live and dead grubs tallied, the "spikes o' death" had killed as many grubs as the diazinon.

"Next, I'd like to study how they work on the golf course," Cranshaw chuckles, though he's really not kidding. He has already shot slides of his father, clad in spiked sandals, practicing a little pest control on the fairway. "If golfers wore them, or shoes with slightly longer cleats, the result might be decent grub control on golf courses with fewer pesticides," he suggests. (If you would like to order a pair of lawn aerator sandals, write: Mellinger's Inc., 2310 W. South Range Road, North Lima, OH 44452-9731.)

Cranshaw used the spikes o' death," lawn aerator sandals, to spear underground grubs.

While his students were spraying diazinon on grub-infested patches of land, Cranshaw was busy walking on the turf in his new sandals.

In the end, he had killed as many grubs as the diazinon. His next step is to try the "spikes o' death" out on golf courses.

THE MENACING HORDE

There's still one Colorado pest Cranshaw hasn't settled with. He refers to it as the green-yellow horde, so menacing and destructive some years that it almost defies conventional controls. Colorado gardeners know it as the implacable plains grasshopper.

"The hoppers are so bad some years that they make gypsy moths back East look like beneficial insects," Cranshaw declares. "You could spray Sevin everyday, and even if it does kill them, there will just be scores more coming over the fence tomorrow."

Three summers ago, phones at the Extension office were ringing off the hook with frustrated calls from hopper-besieged gardeners. In the madness, Cranshaw and a few students decided that perhaps the answer really wasn't to fight the insect after all. Since Biblical times, other cultures have learned to "coexist" with the grasshopper, so why not Americans?

For this experiment, Cranshaw gave his unforgettable rallying cry:

"If you can't beat 'em, eat 'em." Eventually, eight reluctant students and faculty members heeded the pleas The point of the experiment was to determine the most palatable species on the Plains. After all, differences in taste do exist, Cranshaw contends.

A Korean student, used to eating grasshoppers as snack food in his homeland, once told Cranshaw that Koreans prefer one species above several others for flavor. Participants had no reason to doubt him, of course. But for this first round, they could muster the appetite for only two species. During a midday luncheon, they prepared about 100 male and female hoppers two ways. Brittle wings and legs were removed (they reportedly get caught in your teeth) and the hoppers were either roasted and salted or dipped in tempura batter and soy sauce.

Overall, the roasted males of both species proved tastiest, everyone concurred. Then again, no one volunteered to take home the leftovers, and Cranshaw hasn't had requests to repeat the trial. So the group's unanimous conclusion stands: For the near future, at least, controlling grasshoppers by eating them isn't likely to catch on in the States.

The same no doubt holds true for cabbage loopers, even though Cranshaw compares their flavor and texture to shrimp. He tasted them once in graduate school at the University of Minnesota while working on pest problems for commercial canned pea growers. "Peopie pay $7.99 a pound for lobster and shrimp, and you don't even want to know what those crustaceans eat off the ocean floor," he contends. "These insects just get to the peas a little before we do, but we wouldn't dare eat them. Ironically, I think they taste a lot better than canned peas in the first place."

What Cranshaw enjoys most about his work is challenging students' prejudices about insects. "People are anxious even talking about insects, and sometimes if you're a little outrageous about bugs, it eases people's fears," he says. He has put together a slide show that proves his point beautifully.

The first shot, intended to startle students, works every time. It's a close-up of a lime-green tomato hornworm, reared up to charge the class like some huge, hideous horned dragon. "The only known function of that ferocious-looking horn is to scare gardeners," he announces, clicking the next slide onto the screen. "Even my youngest son, Bill the baby, knows that. And like most 3-month-old kids, he's a big help in the garden."

The Colorado hopper is one pest Cranshaw hasn't yet settled with.

The next few shots have been staged to feature "Bill the baby," as Cranshaw always identifies him, supposedly performing a few pest-related chores around the garden. Lounging in his car seat, Bill wears a puzzled stare as he casually "handpicks" a hornworm or two, "checks" insect traps, and "volunteers" as a living mulch on weeds. So what's to fear?

"I mean, if Bill the baby can do it, .. ." Cranshaw deadpans, flashing up a second glimpse of the lunging hornworm. This time laughter drowns his words, and the point hits home. "Sometimes, the most serious insect damage to humans is psychological, and there are ways to handle that," he concludes. "Which just goes to prove that some insects pose more of a sociological problem than a pest problem. If people don't know any better, they just presume the worst about insects."

That's something Whitney Cranshaw has never done.